Understand team effectiveness

Introduction

Following the success of Google’s Project Oxygen research where the People Analytics team studied what makes a great manager, Google researchers applied a similar method to discover the secrets of effective teams at Google. Code-named Project Aristotle - a tribute to Aristotle’s quote, "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts" (as the Google researchers believed employees can do more working together than alone) - the goal was to answer the question: “What makes a team effective at Google?”

Read about the researchers behind the work in The New York Times: What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team

Define what makes a “team”

The term team can take on a wide array of meanings. Many definitions and frameworks exist, depending on task interdependence, organizational status, and team tenure. At the most fundamental level, the researchers sought to distinguish a “work group” from a “team:”

- Work groups are characterized by the least amount of interdependence. They are based on organizational or managerial hierarchy. Work groups may meet periodically to hear and share information.

- Teams are highly interdependent - they plan work, solve problems, make decisions, and review progress in service of a specific project. Team members need one another to get work done.

Define “effectiveness”

Instead, the team decided to use a combination of qualitative assessments and quantitative measures. For qualitative assessments, the researchers captured input from three different perspectives - executives, team leads, and team members. While they all were asked to rate teams on similar scales, when asked to explain their ratings, their answers showed that each was focused on different aspects when assessing team effectiveness.

Executives were most concerned with results (e.g., sales numbers or product launches), but team members said that team culture was the most important measure of team effectiveness. Fittingly, the team lead’s concept of effectiveness spanned both the big picture and the individuals’ concerns saying that ownership, vision, and goals were the most important measures.

So the researchers measured team effectiveness in four different ways:

- Executive evaluation of the team

- Team leader evaluation of the team

- Team member evaluation of the team

- Sales performance against quarterly quota

Collect data and measure effectiveness

They conducted hundreds of double-blind interviews with leaders to get a sense of what they thought drove team effectiveness. The researchers then looked at existing survey data, including over 250 items from the annual employee engagement survey and gDNA, Google’s longitudinal study on work and life, to see what variables might be related to effectiveness. Here are some sample items used in the study that participants were asked to agree or disagree with:

- Group dynamics: I feel safe expressing divergent opinions to the team.

- Skill sets: I am good at navigating roadblocks and barriers.

- Personality traits: I see myself as someone who is a reliable worker (informed by the Big Five personality assessment).

- Emotional intelligence: I am not interested in other people’s problems (informed by the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire).

Identify dynamics of effective teams

With all of this data, the team ran statistical models to understand which of the many inputs collected actually impacted team effectiveness. Using over 35 different statistical models on hundreds of variables, they sought to identify factors that:

- impacted multiple outcome metrics, both qualitative and quantitative

- surfaced for different kinds of teams across the organization

- showed consistent, robust statistical significance

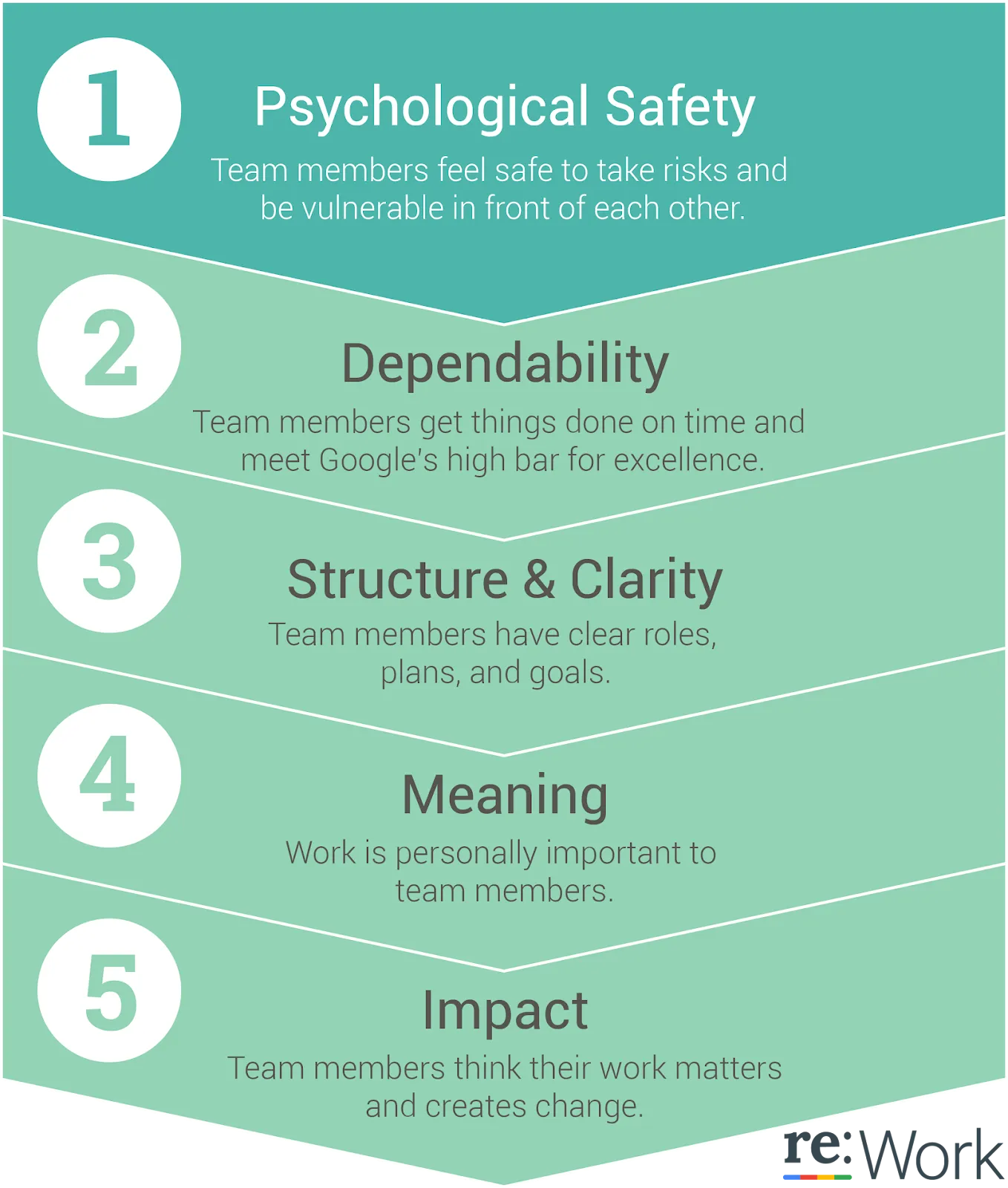

The researchers found that what really mattered was less about who is on the team, and more about how the team worked together. In order of importance:

- Psychological safety: A strong team culture was correlated with each member’s perception of the consequences of taking an interpersonal risk. Those on teams with strong cultures feel safe taking risks in the face of being seen as ignorant, incompetent, negative, or disruptive. In a team with high psychological safety, teammates feel safe to take risks around their team members. They feel confident that no one on the team will embarrass or punish anyone else for admitting a mistake, asking a question, or offering a new idea.

- Dependability: On dependable teams, members reliably complete quality work on time (vs the opposite - shirking responsibilities).

- Structure and clarity: An individual’s understanding of job expectations, the process for fulfilling these expectations, and the consequences of one’s performance are important for team effectiveness. Goals can be set at the individual or group level, and must be specific, challenging, and attainable. Google often uses Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) to help set and communicate short and long term goals.

- Meaning: Finding a sense of purpose in either the work itself or the output is important for team effectiveness. The meaning of work is personal and can vary: financial security, supporting family, helping the team succeed, or self-expression for each individual, for example.

- Impact: The results of one’s work, the subjective judgment that your work is making a difference, is important for teams. Seeing that one’s work is contributing to the organization’s goals can help reveal impact.

The researchers also discovered which variables were not significantly connected with team effectiveness at Google:

- Colocation of teammates (sitting together in the same office)

- Consensus-driven decision making

- Extroversion of team members

- Individual performance of team members

- Workload size

- Seniority

- Team size

- Tenure

It’s important to note though that while these variables did not significantly impact team effectiveness measurements at Google, that doesn’t mean they’re not important elsewhere. For example, while team size didn’t pop in the Google analysis, there is a lot of research showing the importance of it. Many researchers have identified smaller teams - containing less than 10 members - to be more beneficial for team success than larger teams (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993; Moreland, Levine, & Wingert, 1996). Smaller teams also experience better work-life quality (Campion et al., 1993), work outcomes (Aube et al., 2011), less conflict, stronger communication, more cohesion (Moreland & Levine, 1992; Mathieu et al., 2008), and more organizational citizenship behaviors (Pearce and Herbik, 2004).

Help teams determine their own needs

Beyond just communicating the study results, the Google research team wanted to empower Googlers to understand the dynamics of their own teams and offer tips for improving. So they created a survey for teams to take and discuss amongst themselves. Survey items focused on the five effectiveness pillars and questions included:

- Psychological safety - “If I make a mistake on our team, it is not held against me.”

- Dependability - “When my teammates say they’ll do something, they follow through with it.”

- Structure and Clarity - “Our team has an effective decision-making process.”

- Meaning - “The work I do for our team is meaningful to me.”

- Impact - “I understand how our team’s work contributes to the organization's goals.”

After completing the survey, team leads received aggregated and anonymized scores to share with team members and inform a discussion. A People Operations facilitator would often join the discussion, or the team lead would follow a discussion guide created by the People Operations team.

Foster effective team behaviors

Google researchers found that individuals on teams with a stronger team culture are less likely to leave Google, they’re more likely to harness the power of varied ideas from their teammates, they bring in more revenue, and they’re rated as effective twice as often by executives.

Organizational behavioral scientist Amy Edmondson of Harvard first introduced the construct of “team psychological safety” and defined it as “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.” Taking a risk around your team members may sound simple. But asking a basic question like “what’s the goal of this project?” may make you sound like you’re out of the loop. It might feel easier to continue without getting clarification in order to avoid being perceived as ignorant.

To measure a team’s level of psychological safety, Edmondson asked team members how strongly they agreed or disagreed with these statements:

- If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you.

- Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues.

- People on this team sometimes reject others for being different.

- It is safe to take a risk on this team.

- It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help.

- No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.

- Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized.

In her TEDx talk, Edmondson offers three simple things individuals can do to foster team psychological safety:

- Frame the work as a learning problem, not an execution problem.

- Acknowledge your own fallibility.

- Model curiosity and ask lots of questions.

In promoting the results of Google’s research internally, the research team has been running workshops with teams. In the workshops, anonymized scenarios have been used to illustrate behaviors that can support and harm team effectiveness. The scenarios are role-played and then the group debriefs. Here’s an example scenario:

Link to Youtube Video (visible only when JS is disabled)

Psychological Safety Scenario 1 | Ideas & Innovation

Uli is a long time manager known for his technical expertise. For the past two years he’s worked as manager of team XYZ, which is responsible for running a large scale project. He upholds very high standards, but in the past few months Uli has become increasingly intolerant of mistakes, ideas he considers to be “underpar,” and challenges to his way of thinking.

Recently, Uli publically “trounced” an idea offered by an experienced team member and spoke very negatively about that person to the wider team behind their back. Everyone else thought the idea was strong, well-researched, and worth exploring. Ideas have since dried up.

Uli’s ideas drove the recent project proposal, but it was ultimately rejected by the executives because it lacked creativity and innovation.

Debriefing questions:

- What behaviors do you see that reflect a strong team culture?

- What behaviors may signal that the team is not safe for taking risks in the scenario?

- Why is taking risks so important? What difference does it make in a team? What have you seen on your teams?

If you’re a manager, consider these recommendations when coaching team members and teammates.

Make it your own: Customize the tool below

Help teams take action

Whatever it is that makes for effective teams in your organization, and it may be different from what the Google researchers found, consider these steps to share your efforts:

- Establish a common vocabulary - Define the team behaviors and norms you want to foster in your organization.

- Create a forum to discuss team dynamics - Allow for teams to talk about subtle issues in safe, constructive ways. An HR Business Partner or trained facilitator may help.

- Commit leaders to reinforcing and improving - Get leadership onboard to model and seek continuous improvement can help put into practice your vocabulary.

Team effectiveness:

- Solicit input and opinions from the group.

- Share information about personal and work style preferences, and encourage others to do the same.

- Watch Amy Edmondson's TED Talk on psychological safety.

- Clarify roles and responsibilities of team members.

- Develop concrete project plans to provide transparency into every individual’s work.

- Talk about some of the conscientiousness research.

- Regularly communicate team goals and ensure team members understand the plan for achieving them.

- Ensure your team meetings have a clear agenda and designated leader.

- Consider adopting Objectives & Key Results (OKRs) to organize the team’s work.

- Give team members positive feedback on something outstanding they are doing and offer to help them with something they struggle with.

- Publicly express your gratitude for someone who helped you out.

- Read the KPMG case study on purpose.

- Co-create a clear vision that reinforces how each team member’s work directly contributes to the team’s and broader organization's goals.

- Reflect on the work you're doing and how it impacts users or clients and the organization.

- Adopt a user-centered evaluation method and focus on the user.